Joe Ulrich remembers sleeping in the basement of the rickety Bliven Mansion in Livingston as a kid totally creeped out knowing that western outlaw William Mason “Bill” Dalton had been buried just feet away. The story passed down was that Dalton – a member of infamous bands of outlaws who terrorized Oklahoma in the 1880s and 1890s – was killed in an ambush and shipped by train to his father-in-law’s property in Livingston for burial. When Cyrus and Catherine Bliven moved two years later in 1896, Dalton’s lead casket was exhumed and buried in an unmarked grave at the southwest section of the Turlock cemetery.

The mansion had been constructed in 1889 by wealthy rancher Cyrus Bliven. By the time Joe’s parents, Everett and Helen Ulrich, bought the historic property with its 30 acres after World War II, the house’s dry timbers were old and creaky. Rats balanced on exposed pipes in the cellar and scampered in the attic. Bliven’s daughter, Jane (who also went by Jennie), was romanced by Bill Dalton before their marriage in June 1885. The couple had two children, Charles Coleman Dalton and Grace May Dalton, who were born in Livingston and reportedly lived in the mansion.

The macabre notion of the outlaw’s burial between two palm trees in front of the house isn’t the only thing that transmitted a creepy aura to the property. Bliven was a spiritualist who conducted séances in specific rooms of the house as his guests – coming from all over California – strained through a spiritual veil to commune with the dead.

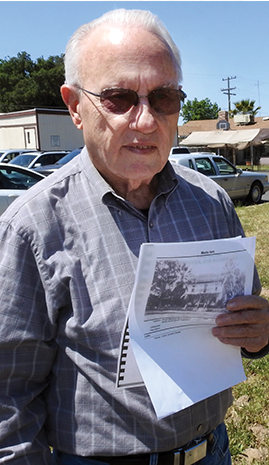

“For a long time it was not occupied. It was considered a haunted house and no one would live in it,” said Ulrich, 87, of Turlock. “There were certain rooms designated spirit rooms and us kids didn’t know much about it when we moved in but we later found out one of the rooms we lived in was a spirit room.”

The Ulrich children hosted sleepovers with their friends “to all get scared together.”

“(Bill Dalton) had already been moved, we thought. We liked to think that maybe he hadn’t so we could be scared.”

The scariest memory came when he moved his bedroom into the cellar, just feet from the once earthen void filled by a desperado and his coffin.

“It was a spooky place anyhow because of Bliven’s reputation.”

Neither the Ulrichs – nor the town of Livingston for that matter – were awed by the historical significance of the mansion and it was razed in the late 1940s. Some of the lumber went into a home on Second Street, which has since been moved.

“It was getting old and rickety. Actually rats were running through the walls at night and I’d be sound asleep and we’d hear this racket that sounded like a herd of horses. The bees had penetrated and they found bee hives all over the place when they tore it down. I think my folks were afraid of a fire. It was a terrible shame; it would have made a great museum. My dad was a farmer and they didn’t really appreciate the historical significance. Looking back now, it is a shame it could not have been preserved.”

The Bliven Mansion lot is now occupied by the Emmanuel Baptist Church at 1310 Main Street.

Despite a lack of cemetery documentation verifying the presence of Dalton, little doubt remains about Turlock being his final resting place.

“We don’t have any concrete record saying that, yes, he’s in that Blevin plot,” said Scott Atherton, a Turlock historian and general manager of the Turlock Memorial Park. That’s not surprising given that the cemetery didn’t hire its first caretaker until 1905, and early records were either lacking or burned in the fire that consumed the Osborne Store where they were being stored in the early 1930s.

Franklin S. Farquhar, author of the 1944 “History of Livingston,” reported visiting the Bliven family plot on Memorial Day in 1930 and bumping into Bill’s widow. By then Jane had been widowed a second time by second husband, Robert Frank Adams, and was living in Richmond. Jane confessed to Farquhar that she was Bill Dalton’s widow but was “adamant to all inquiries.” The Turlock graveyard also bears Mr. Adams’ 1930 grave and is the final resting place for her son Frank C. Adams by him. Jane died Nov. 3, 1941 in Contra Costa County.

The Dalton brothers were raised in a large family of mostly well-mannered siblings. However, four of the 15 children loom large in western outlaw folklore: Grat, Bob, Bill and Emmett Dalton. Littleton “Litt” Dalton, who was a good and hard-working citizen, believed that his younger siblings became lawless because of the bad influence of their father, James Lewis Dalton, who was a failure as a gambler – he brought his beat-down race plug into the Central Valley not long after the railroad was introduced in the early 1870s – and introduced the four to “the worst riff-raff in the country,” said Litt. Their mother, Adelina Lee Younger Dalton, also had become lax in child rearing and refrained from spanking the boys as she did the older ones. Grat was described as the worst, often throwing a fit if he lost while gambling. The brothers may have also been influenced by their cousins, the Youngers, another well-known outlaw gang. They eventually became heavy drinkers, which may account for their insatiable thirst for easy money.

Many of the Dalton brothers came to California in 1880 looking for ranch work. Litt recounted how he received an education while working at the Turlock Hotel operated by Eliza Allen Strean and son Stonewall Jackson “Stoney” Allen. Today the Jack in the Box restaurant in downtown Turlock occupies the hotel site. Some sources say that Bill Dalton himself worked at the hotel a while. Cole and Grat Dalton found work cutting oak trees on a ranch a few miles east of Hills Ferry. Bill came to California to work there as well on the Turner and Stevinson ranches southwest of Livingston. He then worked for the Bliven family which owned a ranch near Estrella and one at Central Camp six miles south of Livingston.

Bill Dalton was described as the life of a party, a good looking charmer who enjoyed music, playing guitar, singing, dancing and practical jokes. He delighted in re-telling others how he hid a dead cat, stuffed in a shoe box, inside the Livingston saloon where Grat was a bartender. The box with the decaying carcass was hidden among some dust mops and the stench grew to the point that customers stayed away – until Grat realized the source and removed it.

Accounts of Bill as a state legislator do not bear out in historical records. However, reports of him being active in the Democratic Central Committees in San Benito and Merced counties may be more truthful.

The Dalton legacy got off to its ugly origins when, on Feb. 6, 1891, a Southern Pacific train was commandeered by armed robbers near what is now Earlimart in Tulare County. Separating fact from fiction is difficult given the inaccurate newspaper reports of the day but it’s generally believed Emmett and Robert “Bob” Dalton staged the Alila robbery. They gained access to the express car and in an exchange of gunfire locomotive fireman George Radliff, 26, was fatally shot. Convinced that the Daltons did the job, Tulare County Sheriff Eugene Kay spent months following clues and hunting them down. Assisted by Bill Dalton, Bob and Emmett managed to ride to freedom from Ludlow, and eventually to their mother’s house in Kingfisher, Oklahoma via Mexico.

The association with their brothers led authorities to arrest both Grat and Bill Dalton. At the time, Bill was farming wheat near Cholame (which would later gain fame as the place where actor James Dean was killed in a 1955 car crash). Bill was exonerated of all charges. Despite having an alibi that he was at a Fresno hotel during the robbery, Grat was found guilty on June 7, 1891 after an unfair trial in Visalia. Before his sentencing date, Grat escaped jail – some say Bill helped – on Sept. 26 and hid out on what is known as Dalton Mountain east of Sanger. Sheriff Kay and others engaged Grat in a December 1891 gunfight but he escaped and made his way back to Oklahoma.

Bill’s name had been forever tarnished. When a southbound train was robbed on Sept. 3, 1891 in Ceres – near the vicinity of today’s Mitchell Road off-ramp – Bill Dalton and friend Riley Dean were the primary suspects. Ceres train robbers had tried to blow open the express car with dynamite and exchanged gunfire with Wells Fargo Detective Len Harris who survived a bullet wound to the neck. Dalton was arrested near Traver, held in the Visalia jail and then brought to the downtown Modesto jail by the Stanislaus County sheriff. After hearing the conflicting testimony of railroad detectives, Stanislaus County Superior Court Judge Loren W. Fulkerth dismissed Dalton’s charge during his preliminary trial. Detectives later pursued Christopher Evans and John Sontag for the Ceres robbery.

Twice wrongly accused of Valley train robberies, Jane reported that her husband left Merced County for Oklahoma on Nov. 15, 1891 to be with his family. The Weekly Oklahoma State Capitol, a publication of that day, quoted Jane Dalton as saying: “We kept up a regular correspondence, and though he requested me to address him under various names, I had no thought that he was living other than an honest life.”

Historians are uncertain about Bill Dalton’s participation in all of the Dalton train robberies in 1892, 1893 and 1894 in Oklahoma Territory.

Jane was shocked when she and the children arrived in Kingfisher, Okla., in September 1893 and Bill didn’t meet them at the train station. He showed up the next night, armed to the teeth which triggered Jane’s suspicions. “When I asked him why he wore the pistols,” Jane was quoted, “he laughingly replied, ‘Oh, it is just for style.’”

What Jane couldn’t have known is that Bill had just participated in a bloody Sept. 1 gunfight at a saloon in Ingalls, Okla., where the gang was surrounded by lawmen. Dalton allegedly shot to death Deputy Marshal Lafayette Shadley in order to escape. As Bill Dalton’s name began appearing in newspaper reports of robberies, Jane grew concerned that her husband was living a dangerous double life.

Historians still debate Bill Dalton’s role in the legendary Oct. 5, 1892 Coffeyville, Kansas raid on two banks committed by his brothers Grat, Bob and Emmett. One theory has Bill camping outside of town but not participating. Their courage bolstered by hard drinking, the Daltons approached the two banks accompanied by gang members Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers. On alert from an earlier law enforcement tip that the Daltons were planning a job, merchants sensed trouble when the men, wearing fake beards, approached. Townsfolk armed themselves and fired upon the bandits as they tried to escape with cash. After the smoke cleared, eight were dead including four town defenders. Emmett was badly wounded but survived. Lined up on the wooden sidewalk next to the bank like prized game, the bodies of Bob and Grat Dalton, Broadwell and Powers were a grisly display for gawkers and photographers.

Bill Dalton accompanied his mother to bury his dead kin and lashed out at authorities for storing the bodies in a heap on a jail cell floor where the display continued for bloodthirsty locals. Bill claimed the bodies were robbed of their dignity as well as cash they had earned.

The brothers’ fate did not sway Bill Dalton’s lawlessness. Instead, Bill teamed up with Bill Doolin to form the Doolin-Dalton Gang, also known as the Wild Bunch or the Oklahombres, to rob banks, stores and trains in Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas and the Oklahoma Territory even though it’s unlikely Dalton participated in all of the gang’s robberies. Dalton created a new and final gang of his own in March of 1894.

In late spring of 1894, Bill and Jane settled on a ranch outside of Pooleville, Okla., on land owned by the Wallace family. One of Bill’s new gang members was Jim Wallace. Bill announced to Jane that he was taking a trip to Texas. On May 23, 1894, some 265 miles from home, Bill Dalton and gang members Wallace, Charles White, Big Asa Nite and Jim Nite mounted as assault on the First National Bank of Longview, Texas. As in Coffeyville, a fusillade of bullets flew as the robbers exited the bank. Dalton fled but Wallace was killed, his body hung on a flagpole. The sheriff collected key evidence – a hat that was marked, “W.O. Dustin, Ardmore, I.T." – that would circle back to Dalton. Longview authorities telegraphed the U.S. Marshal in Ardmore and gave a description of the dead man who proved to be Jim Wallace who lived in Pooleville.

Bill returned home on May 30, 1894, allegedly with plenty of money. Jane and an acquaintance went shopping but were picked up for illegally trying to receive contraband whiskey – and used an alias as a Mrs. Brown and a Mrs. Pruitt, respectively. Authorities surrounded the Dalton cabin on the morning of June 8, 1894 and fatally shot Bill, as he jumped from a window, armed, as he made his way to a creek. He was shot twice, the .44-caliber slugs probably still in the Turlock grave. Evidence of the robbery, including $1,700 in cash and Longview bank bag, were found hidden in the home.

Dalton’s body was embalmed and taken by train to Ardmore where throngs gathered to see the dead outlaw. Jane accompanied his body by train to Fresno and then Livingston where a funeral was attended by thousands on June 22, 1894. The body was buried at the left front corner of the house, likely the weed-covered patch of ground adjacent to the church parking lot.

When Cyrus Bliven either lost or sold his property, a decision was made to dig up the body and move him in the cover of the night to the Turlock cemetery.

Fanciful stories muddle the Dalton story. For example, the July 27, 1936 edition of the Turlock Daily Journal carried the wild claims of Stevinson rancher William Virgo that the Daltons may have buried gold coins on Turner Island where they lived in a bunkhouse. Virgo claimed a man resembling Emmett Dalton – this was in 1927 after Dalton was released from prison – was nosing around and inquiring as to the location of Salt Slough.

Eager to sell papers some reporters filled in the blanks about Bill Dalton’s life with stories that couldn’t have been true, including one that claimed Bill Dalton was in Chicago to talk to Frank James about opening a saloon at the same time he was in Texas robbing a bank.

Others say the man killed in the Oklahoma shootout was not Dalton. The theory makes no sense given that Jane Dalton did bring a man’s body to Livingston and postmortem photos of him match portraits taken in Coffeyville.

Atherton said evidence wholeheartedly supports Dalton’s burial in the Turlock cemetery. Records show the Blivens purchased six graves within the family plot with four occupied by Cyrus (who died in 1902), wife Catherine, and two children, W.B. and Liu. The cemetery staff recently probed the ground of the Bliven family plot to pinpoint a hard object – presumably the lid of Dalton’s heavy lead coffin. That leaves one grave closest to the West Main Street sidewalk empty, probably because a wrought iron fence and sidewalk encroached upon it.

Editor’s note: For more on Bill Dalton’s grave, check out a YouTube video produced independently by the author. Search for “Bill Dalton’s grave” or type in this URL: https://youtube/GtkHMMYOneY