Oh what a Hollywood blockbuster the events of August 14, 1889 in Lathrop would make.

The Lathrop train depot no longer stands but a historical plaque was once in place across the street at 7th and K streets to recount the story until thieves carried it off.

The shooting rocked Lathrop, a small settlement of a store and schoolhouse prior to construction of the Central Pacific Railroad around 1870. Originally named Wilson’s Station, the town was renamed after railroad financier Leland Stanford declined being the namesake for the railroad stop west of Manteca, and his wife’s maiden name of Lathrop was selected. Lathrop wouldn’t become an incorporated city until 1989 – long after Terry’s murder was forgotten in the Stockton Rural Cemetery.

On August 14, 1889 a train pulled into the station with the two dignitaries aboard. The colorful David Terry and his wife Sarah had a dubious reputation. In his first year of service on the state Supreme Court in 1856 Justice Terry stabbed a person in the neck with his Bowie knife. Three years later the hot-headed Texas native shot to death U.S. Senator David Broderick in a September 13, 1859 duel prompted by an offensive remark Terry made against Broderick. And while duels were considered an honorable way of settling disputes, Terry answered in court for the shooting but was acquitted of murder. Still, he was deemed a villain by many and resigned from the state’s highest court and left San Francisco to set up law offices in Stockton and Fresno.

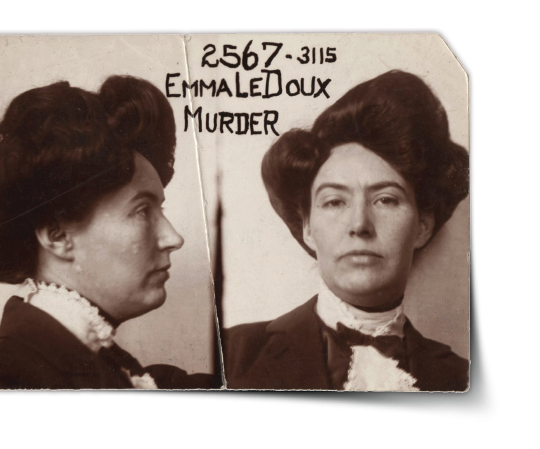

In the 1880s Terry got involved and married a female client that matched his quick temper. Sarah Althea Hill made headlines because of her soured relationship with wealthy Virginia City mine baron and U.S. Senator William Sharon that found its way in court – over money, of course.

At the time of their relationship – Hill was 30 years to Sharon’s 60 – he was making over $100,000 per month. The sugar daddy paid Sarah $500 a month and for her adjoining room in the San Francisco Grand Hotel where he lived. They enjoyed companionship for a while but after a year of being together, Senator Sharon wanted to end the relationship, no doubt due to mental instability. She was explosive and known to carry a small-caliber Colt revolver in her purse and did not hesitate to threaten anyone who crossed her.

He finally evicted her from the hotel room by having the carpets ripped up and the door hinges removed and tried to get her to go away with a payment of $7,500 – the equivalent of around $218,000 today.

In a day when stalking wasn’t a crime, Sarah kept showing up at his office and pleaded for him to reconsider his decision.

When Senator Sharon began a relationship with another woman, Hill sued him for adultery, claiming they were married. She hired attorney and former Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court David S. Terry. Sharon countersued, claiming that the marriage contract she produced was fraudulent.

Sharon v. Sharon dragged on in the courts for years and involved 10 state Supreme Court decisions, 10 Circuit Court decisions and two U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen J. Field, a Lincoln appointee, was assigned to assist the California Circuit Court and preside over Sharon vs. Sharon. Ironically, it was Field who replaced Terry on the California Supreme Court following his 1859 resignation following the duel.

The legal fight ramped up after William Sharon died on Nov. 13, 1885. His son Frederick and his son-in-law fought Hill, who produced a spurious handwritten will – it gave her all of Sharon’s estate – which she claimed to have found in his desk.

Meanwhile, Hill and Terry became romantically involved and eventually married.

In January 1886, a circuit judge ruled the marriage contract to be a forgery. The Terrys refused to comply with court orders to hand over the marriage contract, and were jailed for contempt.

They returned to court in March 1888, seeking further relief. Oral arguments were heard before Justice Field, sitting as Circuit Court Justice, Circuit Court Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, and District Court Judge George Myron Sabin. Months after the hearing, Judge Sawyer encountered the Terrys on an August 14, 1888 train ride between Fresno and San Francisco. Sarah Terry approached Sawyer and threatened to kill him.

On Sept. 3, 1888, as Field ruled that the will was a forgery, pandemonium broke out in his courtroom. Sarah began screaming obscenities at the judge and fumbling in her handbag for the revolver. Marshal John Franks and others attempted to escort her from the courtroom as David Terry rose to defend his wife and went for his Bowie knife. After the hulking Terry struck the marshal and knocked out a tooth, more marshals drew their guns.

Spectators eventually subdued Terry and led him out of the courtroom as he pulled out his Bowie knife again and threatened all around him. One of the marshals present, David Neagle, put his pistol in Terry’s face and both Terrys were arrested. Justice Field later sentenced both to jail for contempt of court – Terry for six months and Sarah Terry for 30 days.

Both Terrys were indicted by a federal grand jury on criminal charges arising from their violent behavior in court.

In July 1889, the California Supreme Court ruled that because Sarah Althea Terry and Sharon had kept their alleged marriage a secret, they were never legally married.

Newspapers reported speculation of a likely attack on Field’s life so Neagle, who had a notable career in law enforcement, was assigned to guard Field.

Neagle previously served as marshal of Tombstone, Arizona after Morgan Earp was wounded in the arm during a March 18, 1882 gunshot.

Terry and Hill were freed from jail and returned to Fresno. As fate would have it, on August 14, 1889, the Terrys boarded a train in Fresno on which Field and Neagle were returning from Los Angeles. At 7:10 a.m., the train pulled into the Lathrop station with the conductor sensing trouble brewing. He sent word for the local Constable Walker to come to the station but he couldn’t be found.

Inside the depot restaurant, Terry spied Field sitting at a table and slowly approached the spectacled jurist from behind. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Terry slapped Field on the cheek while other accounts reported that Terry only attempted to slap Field, or to grab him by his beard.

Neagle, who was only 5-foot-7 and weighed 145 pounds, was not equally matched to the 6-foot-3, 250-pound Terry. Neagle rose from his chair, shouting, “Stop that! I am an officer!” When Terry drew back his fist, Neagle shot Terry in the heart at point-blank range with a .45 caliber revolver. As Terry reeled backward, Neagle fired again, nicking his ear. Neagle announced to 80 to 100 stunned spectators, “I am a United States Marshal and I defy anyone to touch me!”

Field further explained to onlookers that Terry had assaulted him “and my officer shot him.”

Neagle ushered Field to a rail car and locked themselves inside their cabin. Sarah Terry followed and tried to gain entry, saying she wanted to slap Field but Neagle insisted that she stay away or he’d kill her too.

The satchel she had fetched from the train was searched and a pistol was found within it.

Shortly after the shooting, Constable Walker of Lathrop and Stanislaus County Sheriff Richard Purvis arrived. Neagle produced papers issued by the U.S. Attorney General appointing him as a special marshal to protect Justice Field but Walker locked Neagle up in the county jail in Stockton while an investigation took place.

Trying to sort out the facts, San Joaquin County Sheriff Thomas Cunningham telegraphed authorities to detain Field once his train reached Oakland but it didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, Judge Field telegraphed the marshal’s office in Stockton, who relayed information to the U.S. Attorney General. The U.S. Attorney in San Francisco filed a writ of habeas corpus for Neagle’s release.

Sheriff Cunningham, with the aid of the State of California, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, questioning if Neagle legally shot Terry. In 1890, the Supreme Court ruled that federal officers are immune from state prosecution for actions taken within the scope of their federal authority.

After the dust settled, Neagle became a bodyguard and gunman for the Southern Pacific Railroad for several years.

Widowed by her husband’s death, Sarah Terry’s mental condition deteriorated and she aimlessly wandered the streets of San Francisco in disheveled fashion. She constantly spoke to her dead husband. The 42-year-old was diagnosed with schizophrenia and committed to the state mental asylum in Stockton on March 2, 1892 where she spent the rest of her 45 years.

When she died she was buried next to her husband and his first wife in the Stockton Rural Cemetery.

Sharon was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in San Francisco later Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma.

Indeed, what a movie it would make.